You should ask every client where they were born and if they are a U.S. citizen. If they are not a citizen, or there is any uncertainty, you should consult the Immigration Project or other immigration expert.

For the Immigration Project to accurately determine the immigration consequences of a criminal offense, we must know the person’s immigration status. There are different rules and sets of “removal grounds” that apply depending on a person’s status.

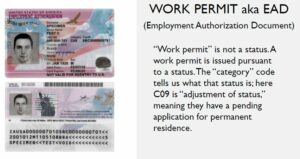

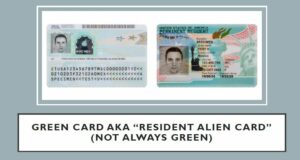

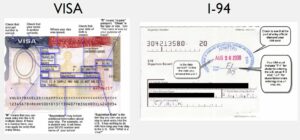

Sometimes the person may not know or may be confused about their status. For example, some people might say “I have [an] asylum” (“tengo un asilo,” in Spanish), when what they mean is that they have a pending application. Thus, it is important to ask for clarification. Sometimes the person will say they have a work permit (“permiso”). A work permit is not a visa or a status. Rather, permission to work is granted pursuant to status, or when a person has a pending application for status. Whenever possible you should get a copy of any immigration identification or paperwork your client has. If you cannot get a copy, ask for the “category” code and “A-number” on the work permit or LPR card. The category code tells us the basis on which it was issued, and the A-number can help us determine if the person is, or has been, in removal proceedings and what the result was.

Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) status, also known as having a green card, is an immigration status that allows individuals to reside in the U.S. indefinitely, provided they do not engage in activities that would violate their immigration status. LPR status is a prerequisite to applying for citizenship.

Important points about Lawful Permanent Resident status:

- Authorization to Live and Work: LPRs have the right to live and work in the United States. They can pursue employment and education opportunities without the need for additional visas or work permits.

- Permanent Residency: The term “permanent” indicates that LPR status is not temporary, unlike nonimmigrant visas. However, it can be lost if the individual fails to maintain certain requirements or engages in activities that violate their immigration status.

- Travel: LPRs are generally free to travel in and out of the United States, but there are certain rules and requirements to follow, including the need to maintain a residence in the U.S. Certain criminal grounds of inadmissibility will apply to LPRs upon return to the U.S.: LPRs with a criminal history should not leave the U.S. without first consulting an immigration attorney.

- Path to Citizenship: While LPRs have the right to live in the U.S. indefinitely, they may also have the option to apply for U.S. citizenship through a process called naturalization after meeting certain eligibility criteria.

Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident status is typically a multistep process that involves sponsorship by a family member or employer, as well as meeting specific eligibility criteria. Asylees and refugees may also apply to become LPRs. It’s important for individuals with LPR status to be aware of the requirements for maintaining their status and to consider the potential benefits of pursuing U.S. citizenship.

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) is a program established in 2012 which permits certain individuals who were brought to the United States while under the age of 16 and who have resided continuously in the United States since June 15, 2007, to remain in the United States and work lawfully for at least two years, so long as they have no significant criminal record and have graduated high school or college or received a degree equivalent. It does not confer any path to permanent legal status and requires renewal every two years. In 2017, the Trump administration attempted to end DACA, but this action was challenged in court. In June 2020, the Supreme Court ruled that the administration’s attempt to terminate the program was unlawful. The Trump administration subsequently tried to impose new limits on DACA, but this action was also challenged in court and a federal judge in New York ordered the administration to set aside the newly imposed limits. Separately, a federal judge in Texas ruled that DACA was unlawful and that no new, first-time applications should be accepted. In January 2021, President Biden issued a memorandum reaffirming the federal government’s commitment to DACA and pledging to appeal the Texas ruling.

Asylum is available to persons already in the United States who are seeking protection based on the same five protected grounds upon which refugees rely. They may apply at a port of entry at the time they seek admission or within one year of arriving in the United States. There is no limit on the number of individuals who may be granted asylum each year, nor are there specific categories for determining who may seek asylum. Asylees are eligible to apply to become Lawful Permanent Residents one year after receiving asylum.

Refugees are admitted to the United States based upon an inability to return to their home countries because of a “well-founded fear of persecution” due to their race, membership in a particular social group, political opinion, religion, or national origin. Refugees apply for admission from outside of the United States, generally from a “transition country” that is outside their home country. The admission of refugees turns on numerous factors, such as the degree of risk they face, membership in a group that is of special concern to the United States (designated yearly by the president and Congress), and whether or not they have family members in the United States. Refugees are eligible to apply to become LPRs one year after admission to the United States as a refugee.

Some undocumented immigrants enter the United States without going through official ports of entry or inspection by immigration authorities (known as EWI, entered without inspection). This could involve crossing the border without authorization, either by land, sea, or air.

Undocumented immigrants do not have legal immigration status in the United States. They are not authorized to work, and they can be subject to detention and removal (deportation) proceedings if discovered by immigration enforcement agencies.

A person who enters the country lawfully, on a temporary visa, but then remains in the country after the expiration of the visa is undocumented. Similarly, anyone who loses lawful status but remains in the country is undocumented.

Undocumented immigrants do not have legal immigration status in the United States. They are not authorized to work, and they can be subject to detention and removal (deportation) proceedings if discovered by immigration enforcement agencies.

A U visa is a nonimmigrant visa category created by the United States Congress to provide temporary legal status to victims of certain crimes who have suffered mental or physical abuse and are willing to assist law enforcement in the investigation or prosecution of those crimes. The U visa was established as part of the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (VTVPA) in 2000. The U visa provides a pathway to LPR status.

A T visa is a nonimmigrant visa category created by the United States Congress to provide temporary legal status to victims of human trafficking who have been subjected to severe forms of trafficking in persons and are willing to assist law enforcement in the investigation or prosecution of the trafficking crime. The T visa was established as part of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) in 2000. A T visa provides a pathway to LPR status.

SIJS stands for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status. It is a unique immigration classification available to certain immigrant children who have been abused, abandoned, or neglected by one or both parents, and who cannot be reunited with a parent due to abuse, abandonment, neglect, or a similar reason. If the SIJS application is approved, the youth will be granted Lawful Permanent Resident status.

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) is a designation granted by the United States government to eligible nationals of certain countries that are experiencing ongoing armed conflict, environmental disaster, or other extraordinary and temporary conditions that make it unsafe for their citizens to return. TPS provides temporary relief from deportation and allows individuals to remain and work legally in the United States until conditions in their home countries improve.

To qualify for TPS, individuals must meet specific eligibility criteria, including being a national of a designated country, having continuously resided in the United States since a specified date, and not having certain criminal convictions or being otherwise ineligible. The U.S. government periodically reviews and may extend or terminate TPS designation for each country based on changing conditions.

TPS does not provide a pathway to permanent residency or citizenship, but it does offer protection from deportation and authorization to work legally in the United States for the duration of the designation. Individuals granted TPS must regularly re-register during designated periods to maintain their status.

It’s important to note that TPS is a discretionary immigration benefit granted by the U.S. government and can be subject to changes in policy and legal challenges.

In the context of immigration law in the United States, “parole” refers to a discretionary authority exercised by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to allow certain individuals to enter or remain in the United States temporarily, often for humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit. Parole is not an immigration status like permanent residency or citizenship, but rather a temporary permission to be in the United States.

Parole does not confer any legal immigration status, and individuals granted parole are subject to certain conditions and limitations during their time in the United States.